Bette Gordon grew up watching New York City in black-and-white movies. When she moved there in the late ’70s, she was a visual artist and filmmaker at one of the worst and best times to do those things in the city. Reaganite politics had just led to major slashes in arts funding. Landlords kept buildings empty waiting for big-money buyers.

Gordon, who grew up in Boston and had studied in Paris after she fell in love with Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless, would walk around the city looking for the underworld she had seen in films like Samuel Fuller’s Pickup on South Street and Jules Dassin’s The Naked City. “This city is a city of film noir,” she recalls when thinking back to that initial love for New York. “It’s a city with streets that you’ve seen and imagined, and now I inhabit those streets.”

Artists, musicians, photographers, filmmakers (Gordon included), all lived in sprawling, empty Tribeca lofts, sharing both electricity and ideas. She had a 16mm projector and would throw parties, inviting people over to watch a movie: “It was a good time for making work without the heavy marketplace hanging over you,” she tells me over a phone call that was scheduled to be 30 minutes, but stretches to two hours.

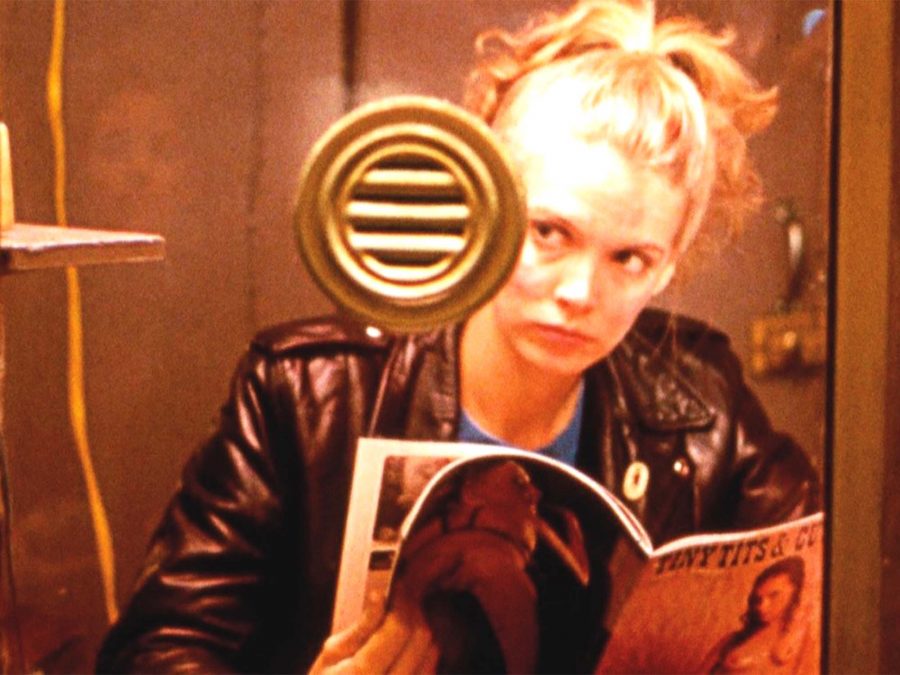

This New York of lofts, creative mingling and pooling of resources is the environment which gave birth to Variety, her 1983 neon-noir feature about a woman who takes a job as a ticket seller at a porn theatre, equal parts repelled and fascinated by the milieu in which she is enveloped. Written by punk author Kathy Acker, shot by future Living in Oblivion director Tom DiCillo, with music by composer John Lurie, and starring Sandy McLeod, Will Patton, Luis Guzmán and Nan Goldin, Variety is a who’s-who of 1980s avant-garde cool.

Gordon was always attracted to the half-lit streets of film noir, the mystery and the darkness, but more so it was the genre’s “female characters who possessed a kind of dangerous and intriguing sexuality” that appealed to her. “In my process of loving these genres of cinema, I thought, ‘What about turning the thriller on its head?’,” she says. “What if the Kim Novak character [from Vertigo] became the investigator and the male character, the Jimmy Stewart one, became the enigmatic figure?”

Her vision of reversing the Hitchcockian thriller was deepened by her random discovery of the Variety Theatre during one of her night walks. “Its neon marquee was something out of the past because I was looking for the past,” she recalls. “I couldn’t stop thinking about this marquee, all lit up in red and green. It was calling me and I couldn’t look away.” A former horse stable turned vaudeville theatre turned nickelodeon in the East Village, the 450-seater went from hosting live action revues to playing porn movies before being turned into an unsuccessful Off-Broadway theatre and, eventually, being torn down in 2005. In the ’80s, it was a cruising spot for gay men. Author and cinema owner Jack Stevenson described it as, “a potent cocktail of old moviehouse karma and rampant sleaze.”

The cinema’s manager allowed her to have the cinema for six hours on a Sunday, and she made Anybody’s Woman for $75, a spoken word experimental short with her pals Spalding Gray and Nancy Reilly. In the film, which is a thematic precursor to Variety, the characters talk about their thoughts on pornography. It’s with this film that she began to sketch the backbone of Variety, and play around with the idea of the monologue. She began modelling her central character, without even realising it, on Kathy Acker.

At this point, the experimental novelist was known for appropriating and remixing the work of other writers such as Charles Dickens and Pierre Guyotat, and she would often perform her own work. Acker’s work is explicit and explosively subversive. Always focused on reimagining language as a feminist tool, her writing was sexually vivid – perfect for Variety. In the film, protagonist Christine’s deadpan description of explicit scenes while her boyfriend listens silently takes direct inspiration from Acker’s refashioning of pornographic language: “She subverted this kind of male language, remaking it for herself, inserting women in that language which she took as her own, as does Christine,” says Gordon.

The filmmaker was also heavily inspired by film theorist Laura Mulvey’s 1975 essay ‘Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema’, which, “really opened me to being able to explore the subject of women and looking.” Variety, in Gordon’s own words, is a film about looking. Christine sits in the free-standing ticket booth all day, “where she can see and be seen.” It uses frames within frames, doorways, windows and reflections to capture the idea of looking and being looked at.

Gordon is fascinated with spaces, and how a woman operates when she infiltrates an intrinsically male space: the baseball game where an enigmatic patron of the cinema takes Christine on a date; and the Fulton Fish Market where she follows him, wandering around a sea of fishmongers and store owners with cardboard signs.

Variety is a document of a contradictory period, a dank New York which boasted a booming artistic underground. Cookie Mueller, artist, writer and one of John Waters’ Dreamlanders, appears in a bit part. And Nan Goldin, already heavily in the scene but not yet the grande dame of portrait photography that she would become, has a supporting role.

“I met Nan Goldin before I knew that I met Nan Goldin,” she says. Still, living in Boston, she was on her way to pick up a friend when she got a frantic call from a woman locked in his Tribeca loft. That woman was Goldin. Some time later, living in New York, she asked her friend and fellow filmmaker Vivienne Dick to shoot a scene for her film Empty Suitcases and was introduced to Nan, properly this time. In the scene Gordon wanted to shoot with her, two women would be exchanging clothes and taking pictures of each other. She asked Nan if she was interested: “Are you kidding? Changing clothes and photography are my passion,” replied Goldin, a relatable genius. Since then, they became close friends and occasional collaborators.

Gordon snuck the photographer into the delivery room when she had her daughter, and Goldin took a picture of her seconds after she was born. When the same daughter got married, Goldin was the wedding photographer. “Living downtown put us in constant contact,” Gordon remembers. There was “music, images and whatever else was going on” at places such as the Mudd Club, Club 57, Danceteria, Tier 3, where they screened each other’s films (and Nan would present her slideshows) in between the band sets. Goldin was photographing then but had not yet made her masterpiece, ‘The Ballad of Sexual Dependency’.

She was the one who introduced Gordon to Tin Pan Alley, the bar where she worked and which would become a major location for Variety: “It was the only place we went when we went uptown”. Gordon still relishes Goldin’s acting in the film Variety (“She was so good, I said, ‘now you’re gonna have a career as an actress!’”) and in 2009 she published a book of photographs from the set of Variety, which also became an exhibition. The book becomes a curious extension of the film, a tangible version of Variety: “My camera and her camera are very similar,” says Gordon, “but the process is very different.”

When they did the book together, Gordon, always driven by narrative, wanted to follow the story of the film; but “that’s not what drives Nan at all. She is driven by images that tell a story.” Grouping the images together, Goldin makes them “follow a visual logic, not a narrative logic. The real collaboration was the movie. It was Nan as a character, Nan as a force. Nan inviting me into her world, me inviting her into mine and the crossover between my lens and her lens.”

Though it is now the subject of many a beautiful essay by feminist cinephiles and screening regularly at film festivals worldwide, the film was originally received “with cheers and boos”. It premiered at the Director’s Fortnight strand in Cannes. The festival wouldn’t accept a 16mm print, so they had to blow it up to 35mm. This and the filmmakers’ trip was paid for by the New York premiere – they rented out Variety Cinema for a whole weekend to show Variety the Movie (“there were lines around the block!”) – and some money producer Renée Shafransky borrowed from a bookie she knew who sold lottery tickets for off-track betting.

“It was a controversial film from the start, more in America than in Europe,” recalls Gordon, trying to pinpoint what exactly riled up people so much. “The most disturbing thing to people was that the ending didn’t provide a conclusion.” Variety ends on a shot of a dark, empty street, the character’s fate left unknown: “Between female desire, which is what the film is about, and gratification lies an empty space, and that space is full of possibilities.”

The post Bette Gordon: ‘Between female desire and gratification lies a space full of possibilities’ appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments