After his dystopian sci-fi THX 1138 failed at the box office, George Lucas was challenged by his friend Francis Ford Coppola to write a film that would appeal to mainstream audiences. Lucas leapt at the proposition, writing a coming-of-age story about four teenagers on the last day of summer in 1962. The script had autobiographical elements, with Lucas using his teenage experiences cruising the strip in his hometown of Modesto, California. He even based some of the characters on parts of his early life, from his street-racing years (John Milner) to his nerdy high school persona (Terry Fields).

Following a troubled pre-production process, Lucas made his film – American Graffiti – at Universal for less than a million dollars. Yet on its release in 1973, it was a massive hit with five Oscar nominations and over $140m earned at the box office. Not only did Lucas’s film meet Coppola’s challenge, but American Graffiti also redefined the teen coming-of-age genre and launched the careers of several stars (Richard Dreyfuss, Ron Howard and Harrison Ford). The commercial success also allowed Lucas to make his next project – a little sci-fi film called Star Wars. The rest was history.

All of these are reasons why, 50 years later, American Graffiti remains arguably one of the most influential American films ever. But the most important reason relates to its innovative use of something that has had a lasting impact on cinema to this day: nostalgia.

While nostalgia can refer to films that are looked up favourably because they were watched during childhood, here it is a force explicitly deployed by Lucas – gazing back towards a specific period and the music, fashion, movies and events that came from it. These tap into the fond memories and positive associations of those in the audience who lived through the era, using the viewer’s sentimental affection to bolster the film’s emotional impact.

Nostalgia is such a potent tool because it is a form of escapism from ageing or the bleak present. If you’re suddenly feeling rather old or unsettled by the modern world, why not watch a movie that captures your teenage years? It helps that the 1950s saw the arrival of popular culture as we know it – shaped by the youth and defined by film, television, celebrity and music. The baby boomers were the first generation to benefit and American Graffiti became the first film to capitalise on their affection for their teenage years.

Whilst there were movies geared towards the teenage market – Blackboard Jungle, Rebel Without a Cause, Beach Party (and the briefly popular beach party genre) – Lucas was going back in time instead of staying in the present.

One of the easiest ways a film can conjure nostalgia is through a soundtrack. In 1973 though, Lucas was going against the grain by loading his film with more than 40 rock and roll, Doo-wop and early R&B songs. ‘That’ll Be the Day’ by Buddy Holly. ‘Johnny B Goode’ by Chuck Berry. ‘Rock Around the Clock’ by Bill Haley and His Comets, set the stage (just like the latter did in Blackboard Jungle). The effect is akin to driving along and suddenly coming across the perfect song on the radio (in fact, in the film they are all diegetic too, with teenagers listening to them via the popular Wolfman Jack show).

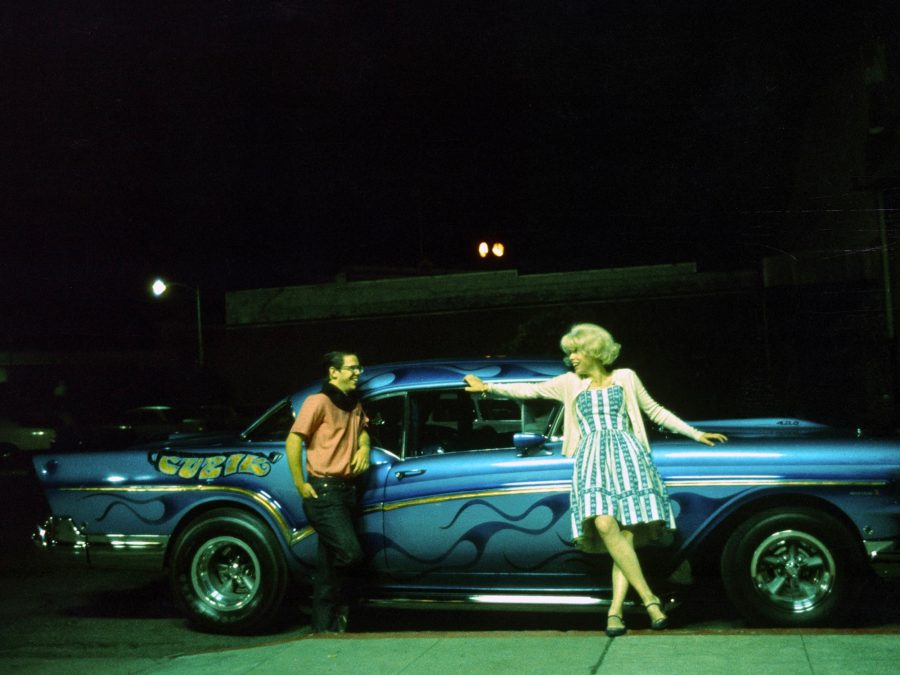

Furthermore, Lucas’ passion for car culture shines as he lovingly shoots the scenes of characters cruising, depicting it as the most vital part of Modesto’s teenage life. As for the classic hot rods, Steve Bolander (Howard) has a 1956 Chevrolet Impala he lends to Terry (Charles Martin Smith). John (Paul Le Mat) drives a modified, bright yellow 1932 Ford Deuce Coupe. And then there is the ’56 Ford Thunderbird, driven by a mysterious blonde woman who Curt Henderson (Dreyfuss) attempts to find.

All of this is a director-specific nostalgia, with Lucas familiarising us with the sights and sounds of his youth. However, it has a reflective purpose too. As Cammila Collar wrote for Outtake, “The very word “nostalgia” denotes not just a fixation with the past, but also a poignant longing for it.” Here, Lucas is longing for a time of hope and innocence that vanished soon after. When Curt is with his ex-girlfriend, she divulges his dream to become a presidential aide and shake hands with John F Kennedy. A year after the events of this film, he was assassinated. By the end of the decade, Nixon was President, the British Invasion had completely changed music, and anti-Vietnam War movements violently clashed with police.

It’s easy then to see why American Graffiti appealed to the baby boomer generation in 1973. After the political strife and instability of the ‘60s, the film was indicative of a desire to return to a simpler time. Even the characters themselves are bittersweetly reminiscing. When John hears The Beach Boys on the radio, he turns it off and remarks that “rock and roll’s been going downhill ever since Buddy Holly died.”

The success of American Graffiti had an immediate impact. One year later, ABC created the hit ‘50s-set sitcom Happy Days (also featuring ‘Rock Around the Clock’ and Ron Howard). In the long term, it preceded a wave of Hollywood films relying heavily on nostalgia for America’s past. Stand by Me contained many references to 1959, from Western TV shows to classic songs from Buddy Holly and Ben E King. Meanwhile, Robert Zemeckis’ Back to the Future travelled to 1955 and depicted it nostalgically. Hill Valley in the mid-1950s is bright and booming; in 1985, it is a run-down shadow of its former self. The past is infinitely better than the present. Together with the 1963-set Dirty Dancing, these films became a defining part of ‘80s Hollywood cinema.

In the 1990s, Forrest Gump ran through the most recognisable events and culture of 20th-century America, from Elvis to the Vietnam War. The film starred Tom Hanks, who would go on to write and direct a tribute to the bygone era of ‘60s garage rock with 1996’s That Thing You Do! Additionally, Richard Linklater’s 1993 high school comedy Dazed and Confused could be considered a ‘70s version of Lucas’ film – set in Austin, Texas in 1976, it also features the director’s home state, a protagonist weighing up his future, and a soundtrack of contemporaneous rock and roll hits.

This penchant for nostalgia has continued well into the 2010s and 2020s. If anything, the digital age has led to an explosion of films looking to the past. In Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Quentin Tarantino replicated California in the summer of 1969 through production design, locations, costume design and soundtrack. But there is a bittersweetness too, with Charles Manson’s cult looming over this fading innocent time. Although Tarantino engages in some alternative history to save Sharon Tate, the whole film is filled with pathos for the people, places and things lost.

Paul Thomas Anderson looked to the ‘70s for Licorice Pizza. Netflix megahit Stranger Things drips with nostalgia for the ‘80s. Greta Gerwig’s Lady Bird and Pixar’s Turning Red became the first major examples of cinema’s nostalgia for the early 2000s, and Lucas’ friend Steven Spielberg leaned into director-specific nostalgia with his autofiction The Fabelmans. Based on his adolescence, the film focuses on how a young Spielberg (renamed Sammy Fabelman) discovered his love for cinema and filmmaking.

The Fabelmans demonstrates how nostalgia has aided a trend from the last couple of years: semi-autobiographical projects. Examples of this include Alfonso Cuarón’s Roma, Kenneth Branagh’s Troubles-set Belfast, and Linklater’s Apollo 10½: A Space Age Childhood. Set in his hometown of Houston in the summer of 1969, Linklater uses animation to take audiences back to his childhood. As a result, it feels like the film is throwing nostalgia at you, listing the boomer-specific music, TV shows and board games that made it, as an adult Stanley (a stand-in for Linklater) reflects in the film, “a great time and place to be a kid.” The semi-autobiographical elements in American Graffiti laid the groundwork for these movies.

Yet decades after American Graffiti’s release, nostalgia continues to be a well-used trait in cinema. Countless filmmakers have approached the past – sometimes their past – with a romanticised, retrospective attitude. Most have followed Lucas in using popular music. Some have even borrowed songs notably used in his film (Back to the Future reuses ‘Johnny B Goode’).

The irony is that American Graffiti ends with a message of looking forward, not back. Out of the film’s central quarter, the one who could be considered the protagonist is Curt, who Lucas said he identified with the most. At first, he’s unsure whether he will join Steve on the plane to a college out east. As he tries to find the blonde girl he saw in the T-Bird, Curt encounters the lives he could live if he stayed: He sees Mr Wolfe, a high school teacher who flunked out of college and now flirts with female students; he spends time with his ex, and he temporarily joins the Pharaoh gang. Most importantly, he meets Wolfman Jack, who tells Curt to move on (“It’s a great big beautiful world out there”).

In the end, Curt takes Wolfman Jack’s advice. He is the only one who gets on the plane to college (Steve remains in Modesto with his high school sweetheart). During the credits, ‘All Summer Long’ by The Beach Boys plays – the same band stuck-in-the-past John hates – as Curt flies to his future. His journey proves American Graffiti is ultimately a coming-of-age story about change over comfort, and choosing the wider world over your hometown. The yearning for what was fades into anticipation for what will be. Cinema may always have an eye on the past – rekindling past decades and childhood memories – but times inexorably change. You can’t stay 17 forever.

The post American Graffiti and the lasting impact of nostalgia on cinema appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments