To this day, I cannot cross a one-way street without looking both ways first. Rationally, I know that I have never encountered a car speeding the wrong way down a one-way street in my own life. Still, evidence or logic hasn’t been enough across three decades to counteract the gruesome advice given out at a primary school assembly. My entire year group was told to always look both ways when crossing the street, especially if it was one-way, as drunk drivers are known to speed down them the wrong way and kill children.

As an adult, I can see that this chilling mix of blunt and perhaps overprotective advice is born out of a mixture of care, fear, and maybe just a pinch of covering your own back as a teacher. The long-term effect that this and other precautionary tales had on my psyche have burrowed into my daily adult life. Although verbal tales may have had an impact, the moving image can be even more powerful. If you grew up in the United Kingdom, footage of water poured on a chip pan fire is probably conjured immediately to mind, or the memory of that one episode of 999 with the foolish kid with fireworks in his pocket.

Released in 2020, the BFI’s The Best of COI: Five Decades of Public Information Films Blu-ray collection was a gateway drug into the world of some of the notorious public information films. Established in 1946, the COI (Central Office of Information) produced and distributed thousands of informational shorts like Charley’s March of Time (1948), an animated explanation of the benefits of paying National Insurance, and Design for Today (1965), a visual tribute to the elegance and ingenuity of everyday design. That’s all well and good, but it’s the COI’s warnings about everyday peril and danger that truly fascinate.

Whatever generation you’re from, the COI films undoubtedly hold familiar characters; Dave Prowse as the Green Cross Code Man, Joe and Petunia, Tufty the Squirrel, or Charley the (barely) talking cat. These helpful heroes and comedy characters provided helpful advice on subjects including crossing the road, telling your Mum where you’re going, or calling the coastguard. But why take a soft approach to safety when you can scare the sensible into the next generation with some of the most effective horror shorts of all time?

1973 may have been the year of The Exorcist and Don’t Look Now, but it’s in the short form that some of the year’s most terrifying horror was produced. 1973’s The Spirit of Dark and Lonely Water (commonly known as Lonely Water) is a 90-second masterclass of terror. A Bergmanesque, faceless Grim Reaper voiced by Donald Pleasance delights in how easy it is for children to drown in natural bodies of water.

A blunt and unflinching approach to visualised catastrophe alongside a horrific villain, this particular film is used as a case study on the lasting impression left by the COI films in Andrés Rothschild’s Into Lonely Water. Talking to luminaries including horror aficionado Kim Newman, it is obvious that 50 years on, the clip is far from forgotten. Placing in the top 75 of Channel 4’s 100 Greatest Scary Moments in 2003, Lonely Water has found a new audience in the internet age with 231,000 views on the BFI YouTube channel at the time of writing.

If the intent of a public information film is to imprint on the young mind in a short space of time, the COI filmmakers were particularly inventive. Efficiency is key to the most chilling of the COI films, and 1973’s Sewing Machine employs an on-screen countdown of 60 seconds while a mother busies herself with sewing. The reveal is that the timer is counting down the final minute of her daughter’s life, as another chilling voiceover reminds the audience to keep watch over children when they’re near traffic. 1975’s Grain Drain is a perfect example of the use of visual metaphor; a doll is used to demonstrate how easy it would be to suffocate in the quicksand of a grain silo, featuring a harrowing vision as the fake body disappears.

Perhaps the master of the COI horror form was John Mackenzie, best known for later directing the bombastic Bob Hoskins gangster classic, The Long Good Friday. A few years prior, Mackenzie directed one of his masterworks, 1977’s Apaches. Having grown up near farmland, it is a film that I thankfully saw for the first time as an adult, thanks to a curious recommendation in Edgar Wright’s 1000 Favourite Movies list. An expansion of the farm-horror sub-genre, Apaches is a veritable Faces of Death of fatal farmyard hazards to children.

An epic opening shot displays a group of silhouetted children emerging over the horizon. The kids are out to play and choose to make the local farm the site of their games. Inspired by TV and films, the children play cops and robbers and the rather outdated ‘Cowboys and Indians’ that inspires the title of the film. Aside from their lack of sensitive representation, the children are used as a precautionary tale of playing in and around the dangerous farm. Their punishment is being dispatched one by one in a string of death sequences worthy of any horror classic.

The surprisingly gruesome child deaths include being crushed, a particularly harrowing poisoning, and perhaps the most infamous of all, a boy who slips and drowns in a pool of pig faeces. It is a relentlessly bleak precursor to Final Destination as the tension and expectation of how and when the next child is going to be killed builds, with Mackenzie even throwing in red herrings like moving vehicles and meat hooks. Tense, suspenseful, shocking and macabre, in 21 minutes, Apaches achieves more than most horror feature films and most certainly leaves a viewer unlikely to play in a barn.

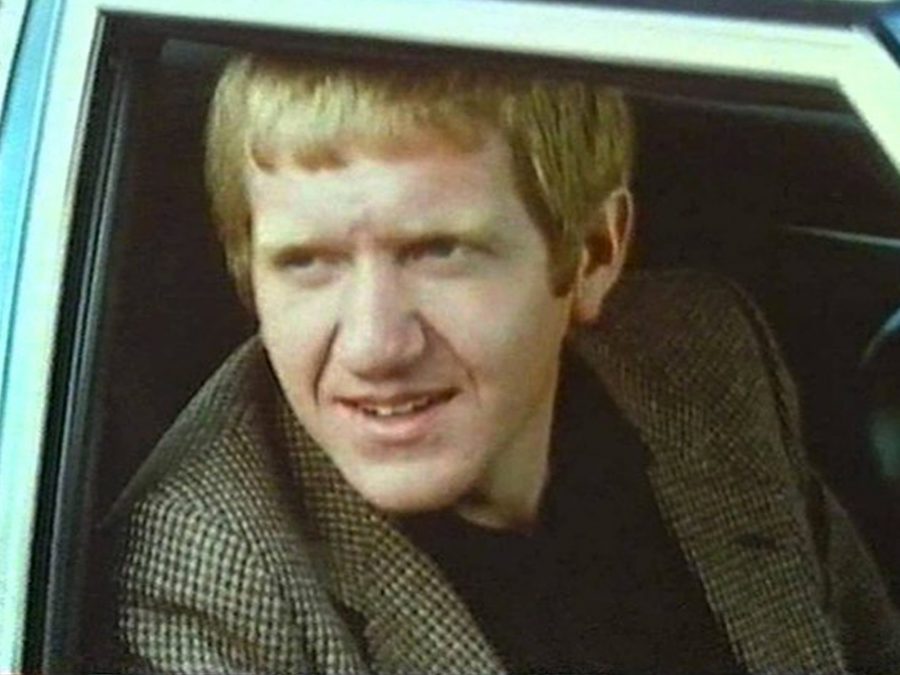

Even after feature film success with The Long Good Friday, Mackenzie would return to helm Say No to Strangers (1981), an entry into the Stranger Danger sub-genre of leary men in cars offering sweets and promises of kittens and puppies to children outside of school grounds. It’s an impressively star-studded affair in retrospect featuring Brenda Blethyn, Bernard Hill, and even Timothy Spall as a Rubik’s Cube-juggling perv. It’s another psychological chiller, albeit one less gruesome than Apaches.

TV’s Duncan Preston abducts a young girl, and as her distraught parents work with police to search for her, the film presents a series of scenarios in which children must decide whether the on-screen kiddies are right or wrong. Should they accept money from a man in the park? Should they tell the police that Timothy Spall is way too old to be hanging around with young kids? Once these questions are asked, thankfully the young girl is returned home safely.

However, considering the film is aimed directly at children, it is the film’s final scene that goes full-tilt horror. As Preston drives around looking for a new target, the narrator delivers the chillingly blunt final line: “You don’t want to end up dead or in hospital. You know what to do: say NO to strangers!” As the narrator speaks, Preston looks directly into the camera, and the film freeze-frames capturing his menacing stare. Pure nightmare fuel.

The closure of the COI at the end of 2011 saw the official end to this filmic factory of horrors. One can’t help but wonder how terrifying they might have made public safety films about COVID, vaping, or meeting strangers on Minecraft. It is rare these days for a modern horror film to keep me awake at night, yet Apaches and the childhood trauma of info-terror continue to live in my mind rent-free.

The post FYI: The true horror of the public information film appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments