Christmas time in the late 1990s: a family and friends sit around the kitchen of a council flat somewhere in south London. Val, played by the great Kathy Burke, is talking about her incarcerated little brother Billy; he’s just had to move cells after being stabbed by another inmate wielding a toothbrush wrapped in razor blades. The screws have moved Billy to the “fraggle wing” — “with all the nonces and the rapists and that… poor sod,” sniggers spread around the room. Then Val drops the punchline: “Mind your backs!” And they’re pissing themselves.

This is the final scene from Nil By Mouth, a 1997 film directed by Gary Oldman that deals in domestic abuse, drug addiction and poverty in working-class Britain. In its most chilling scene Ray Winstone’s alcoholic drug addict Raymond accuses Val, his partner, of behaving unfaithfully, then reacts with horrific violence when she denies it, while their infant daughter watches from the stairs.

Yet despite its harrowing violence Nil By Mouth is also darkly funny, as evidenced by its caustic closing scene. “You always look around the audience and there’s big smiles on people’s faces,” says Charlie Creed-Miles, the Nottingham-born actor who played Billy in the film. “To me that’s like one of the purest moments of where something really dark is turned into a joke. And that’s what people who struggle with adversity in their lives have to do, and I think that’s something the film really captures beautifully.”

Nil By Mouth won two BAFTAs, Burke won Best Actress at Cannes and, in 2017 a Time Out poll of 150 movie experts placed it at number 21 in a list of the greatest British films ever made. It also contains more uses of the word ‘cunt’ than any other film in history (82). “That’s a record we can be very proud of,” says Creed-Miles. “One of my favourite lines in the film is ‘Get in the cunting car!’. Using ‘cunting’ as an adjective. Top marks to Ray for that one.”

Has there been a better depiction of British working-class life in the 25 years since Nil By Mouth’s release? Or rather, looking back on the end of a century in which portrayals of working-class Britain like Get Carter, The Long Good Friday, Kes and even Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels were major cinematic events, perhaps the question should be: has British cinema forgotten the working class altogether?

Oldman has never directed another film. Having largely funded Nil By Mouth himself, he found studios were reluctant to pay for anything cut from the same cloth. “They don’t want another one of these,” Oldman told the BFI’s Geoff Andrew in October 2022. “They want Four Weddings and a Funeral.”

Working-class communities are now sorely underrepresented by British cinema, by both the stories being told onscreen and the actors telling them. In the last 10 years, cuts to arts funding in schools has led to a drop in kids studying drama at GCSE level, meaning fewer state school kids grow up wanting to act. “Soon the only actors are going to be privileged kids whose parents can afford to send them to drama school,” said Julie Walters in 2014, a sentiment echoed by James McAvoy months later.

In a 2017 episode of The Trip Steve Coogan (himself from a “lower middle-class or upper working-class background”) listed the biggest British actors of the day — Benedict Cumberbatch, Eddie Redmayne, Tom Hiddlestone, Damian Lewis — and asked: “How many of those are Etonians?” Answer: all but one (Cumberbatch went to Harrow). Rob Brydon replies: “You know what no one’s ever noticed? How ‘Eddie Redmayne’ is the kind of name an upper-middle-class girl would give to her pony.”

In 2022 it seems like Walters’ forecast may have come true. Take, for instance, GQ’s recent list of actors in line to play the next James Bond – little more than trivial speculation but a reasonable barometer for the biggest actors in Britain right now: names belonging to privately-educated actors — Harry Lawtey, Jamie Campbell Bower, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Robert Pattinson, Jonathan Bailey — dominate the list.

Back in 2013, Maxine Peak expressed similar concerns about the cost of drama schools to the Guardian, while also speaking out about her lack of patience for self-absorbed method actors: “I get very irate with actors when they talk about how distressing it all is. I mean, it’s only acting.”

Oldman raised a similar point at the BFI when discussing his vampiric lead role in Francis Ford Coppola’s Dracula. “I slept in a couple of times,” he said. “Is that method?” He confirmed that none of his preparation involved drinking blood. Is it mere coincidence that the declining numbers of working-class actors has run concurrently with Hollywood’s recent reckoning with the Method, epitomised by Jared Leto’s condom-wielding turn on the set of Suicide Squad?

Oldman also noted the Britishness of keeping working-class talents from the biggest roles, arguing that, if Dracula had been made in Britain, he’d have been cast not as the Count, but as his deranged servant Renfield. It seems as though Britain’s next generation of working-class actors may have wised up to this. Once upon a time actors like Oldman, Walters, Tim Roth and (before them) Michael Caine would move to Hollywood only after making their names in gritty films about real British life.

Today’s equivalents — Daniel Kaluuyah, John Boyega, Jodie Comer, Olivia Cooke and (before them) Idris Elba — either spent their early careers toiling in TV and theatre or forwent the British industry altogether. Perhaps our one true anomaly is Stephen Graham, who entered public consciousness after acting in British films Snatch and This Is England, having studied at an acting college in south London simply because Gary Oldman was among its alumni.

What impact does the film industry’s class imbalance have on the kind of cinema we’re watching? Apart from the obvious, much-reported overload of superhero franchise flotsam in Hollywood, a lack of working-class stories on the silver screen could mean audiences grow up unaware of the problems faced by society’s poorest communities. After 12 years of austerity at the hands of a government now led by a prime minister who once admitted he had no working-class friends, cinema could play a role in the gap between society’s rich and poor becoming unbridgeable.

But even in a purely artistic sense we should decry the decline of working-class cinema as film fans. Oldman, Winstone and Roth all cut their teeth acting under the great Alan Clarke — in Scum, Made in Britain and The Firm respectively, works so honest, visceral and funny they’re still revered by British actors today.

Creed-Miles remembers watching Winstone in Scum while he was growing up. He was in his early twenties when he heard Oldman was directing a film on home soil. “For a long time I was getting jobs like ‘Thug 2’ and ‘Mugger 1’ and ‘Skinhead 5’,” he says. “When Nil By Mouth came along, everyone I knew was aware of it happening, ‘Gary Oldman’s doing a film in London!’ Everyone wanted to be in it. But I managed to nick the part.”

When it came to directing, Clarke was Oldman’s clearest inspiration. At the BFI in October he remembered making a habit of checking on his actors between takes, ensuring cups of tea were provided in make-up trucks and so on – “and that was this thing that Alan did.” Oldman doubled down, going as far as describing some directors he’s worked with as pigs. Clarke was different – looking after actors and listening to their ideas – and Oldman wanted to be like him.

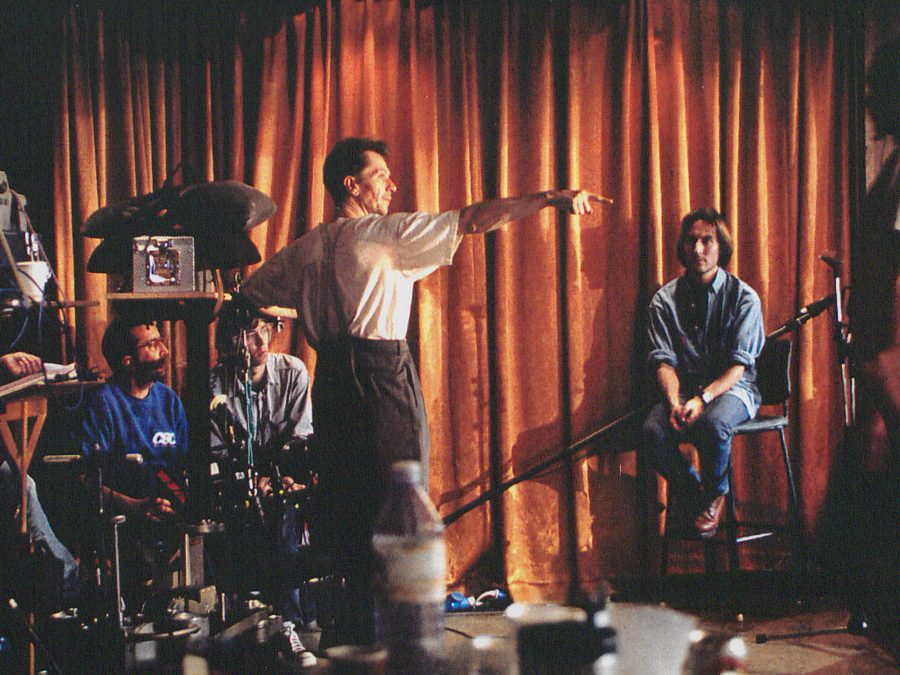

On Nil By Mouth every cast member was mic’d up, meaning they were free to talk over one another during takes, leaving sound designer Jim Greenhorn to piece it together later. Oldman insisted on extensive rehearsals before scenes, a rarity in film. As actors did their lines he encouraged improvisation, taking anything he liked and adding it to the script. Creed-Miles reckons Oldman even filmed some rehearsals without his actors’ knowledge and that footage in the final cut.

In interviews around the film’s release Oldman spoke about the dearth of real stories in contemporary film. “One would imagine that cinema started with Reservoir Dogs,” he said. “People coming in and shooting each other up and it’s all trendy and wisecracking and it’s absolutely sod-all to do with life. It’s movies imitating movies imitating movies imitating movies.”

There are, of course, exceptions to the working-class film drought. Take Ashley Walters’ name-making appearance in Bullet Boy (2004), or his equally good turn as a crack addict in the severely underrated Sugarhouse (2007). Fish Tank (2008) featured a young Katie Jarvis, who was cast despite having no acting experience after an assistant to director Andrea Arnold saw her arguing with her boyfriend on the streets of Tilbury. Then there’s I, Daniel Blake (2016), which won the Palme d’or and made such an impact it was discussed on Question Time, and just last year Adeel Akhtar and Claire Rushbrook lit up Clio Barnard’s Ali & Ava, dancing on mattresses and car rooftops to the sound of UK techno.

These films are not great because they’re about working-class people. They’re great because they tell unflinching stories of working-class life using actors who grew up in it, dealing with the pain, hardship and struggle that comes with living on the breadline.

But it’s not the struggle that makes it. It’s the details. It’s the characters, the accents, the slang. It’s the swearing, the insults, the pubs, the fights, the Ford Escorts, the jungle soundtracks, the Doc Martens, the tracksuits, the pie and mash, the tattoos, the trips to Ibiza, the Marlboro reds, the Staffordshire terriers, the Rotherhithe Tunnel, The Clash, the Stella Artois and the dance routines on the roofs of cars. It’s real life, and it deserves to be recognised on screen. If British cinema loses sight of that, I’d rather read a book.

The 25th anniversary BFI National Archive 4K remaster of Nil By Mouth is available to rent on BFI Player to rent now, and out on limited edition Blu-ray 5 December.

The post Different Class: the decline of British blue collar stories on screen appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments