In 2015, during his widely debated TED talk, American entrepreneur and visual artist Chris Milk described Virtual Reality as “the ultimate empathy machine.” Since then it has become an emergent and rapidly evolving medium in non-fiction filmmaking, but can VR really influence the way we think as individuals, and as a society? How can artists use this technology to create change in the world today? Those were the questions at the forefront of the Expanded strand at this year’s London Film Festival.

The BFI’s immersive art and XR strand screens more than just VR, and showcases a rich selection of works from artists at the forefront of emerging technologies. From augmented reality works like Guy Maddin’s Haunted Hotel in which a series of esoteric collages reveal the manifold permutations of desire and Untold Garden’s Apparatus Lundens, an artificial intelligence-driven experience that asks uncomfortable questions about our digital footprint. There were also immersive audio pieces like Darkfield Radio’s Intravene, a sound experience about the opioid overdose crisis in Vancouver. However, the explosion in both the technical capability and the affordability of virtual reality headsets meant that VR still dominated this year’s program.

One of the main appeals of VR is its ability to drop you directly into other worlds, particularly inaccessible ones, something Dutch artist Dani Ploeger does remarkably well in his latest work Line of Control. Perhaps the simplest, yet most effective piece in this year’s Expanded program, Ploeger’s latest work positions the viewer on the frontline of the Russia-Ukraine war. Using an endless loop of soldiers standing around smoking cigarettes and digging trenches, Ploeger gives us an image of war we’re not used to seeing in cinema; the endless waiting.

One criticism levelled at the use of VR for non-fiction storytelling is that by using a technology used for gaming you run the risk of trivialising the suffering of others. Ploeger is well aware of these concerns, and juxtaposes the stillness of this 360 degree landscape with a terrifying soundscape triggered by the viewers’ eye movement. Whenever you close your eyes, you’re met with the deafening sound of gunfire. Ploeger created this soundscape using archive sounds from films to challenge the spectacle associated with cinematic representations of war and recreate the anxiety of inhabiting a space where violence could erupt at any moment. It might sound odd that in a medium commonly celebrated for its visual capabilities Ploeger would choose to use sound to get his message across, but the act of listening was a common theme in this year’s program.

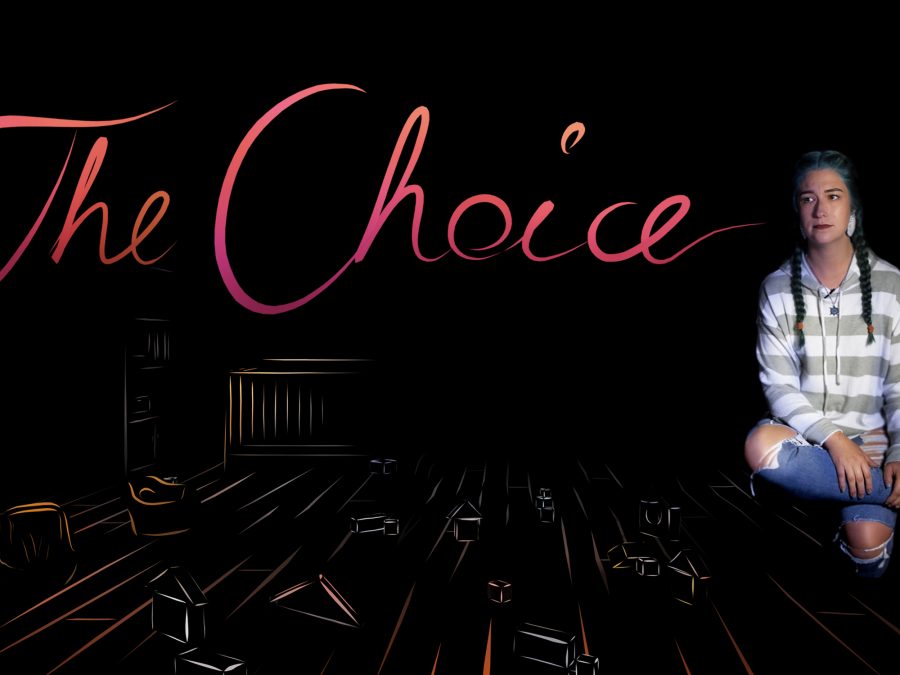

Joanne Popinska’s The Choice, a VR documentary about reproductive rights in the US, also encourages us to lean in and listen closely, taking the form of a conversation with Kristen, a young First Nations woman living in Texas. Sat on a stool directly opposite the viewer, in an otherwise empty space, she discusses the legal obstacles and dehumanising experience she faced seeking a termination. Abortion is arguably the most divisive issue in US politics right now. However, in a recent YouGov poll, one of the main factors behind people changing their minds about reproductive rights was knowing someone who has had an abortion.

The idea that VR can convince people to change their firmly held beliefs on a topic is not a new one, similar claims have been made of cinema for years. However, instead of using the technology at her disposal to recreate Kristen’s story and immerse the audience in her experience, she uses it to create a more direct relationship with her. At certain moments in Kristen’s interview she stops talking and the audience is forced to choose between two questions to ask her. Their selection dictates the direction the conversation takes, providing a sense of agency that transforms the viewer into an active listener.

Despite all the technological advances in VR, it’s still hard to create the feeling that you’re really there, whether watching a movie or listening to someone like Kristen tell their story. To feel really present in a story you need to blur the line between simulation and reality, but that’s hard to do when you’re wearing a clunky headset. When Popinska first screened The Choice, she kept the real-life Kristen hidden in a nearby room so people could give her a hug after they finished the film. But what if the person you were listening to during an experience was sat directly opposite you the whole time?

That’s exactly what happens in Charlie Shackleton’s autobiographical VR film As Mine Exactly, a one-on-one performance piece in which the director sits across the table from the viewer the whole time. Part desktop documentary, part expanded cinema performance, Shackleton projects images and videos from his youth onto the VR screen while he talks directly to the viewer about his mother’s experience with epilepsy, and how viewing her seizures as a young boy has impacted his relationship with documentary filmmaking.

Shackleton was last at the London Film Festival with his film The Afterlight, a cinematic collage in which he brought together a vast ensemble of over three hundred actors who are no longer alive into one film that exists as a single 35mm print that will eventually deteriorate and become lost forever. Performed to one visitor at a time, As Mine Exactly takes Shackleton’s fascination with temporality one step further, and is entirely contingent on the director being present. No one performance is ever the same, with Shackleton using eye motion sensor technology as well as old-fashioned body language to see which parts of the performance the viewer is engaged with and then building the piece around their reactions.

Participating in this performance makes for an unusual experience. Not because of the technology involved, or the presence of the director in the room, but because it’s rare we actually ever listen to someone this intensely. All of us at some point or another have had a conversation where we felt like the other person wasn’t really listening. Perhaps they were looking at their phone or trying to think of a polite way to interrupt you and shift the conversation to themselves. In As Mine Exactly you’re a captive listener. There are no gaps in the conversation for you to interject with your own anecdotes, or breaks in the performance to go to the toilet or grab a drink. For the full thirty minutes you just sit, look and listen.

Much of the power of As Mine Exactly comes from the connection Shackleton creates with his audience throughout the performance. He talks directly to you in a soft and genial manner, generously sharing with you deeply personal memories about his childhood and his relationship with his mother. Wearing a VR headset can often feel like quite a vulnerable experience, but by sharing his desktop with you, Shackleton creates a space of transparency and invites the viewer to experience a new form of intimacy.

This is perhaps most apparent when Shackleton stops speaking directly to the viewer and begins a live conversation with his mother. He performs his lines live, while his mother’s pre-recorded voice plays from a speaker just behind the viewer. They talk about their memories of these seizures, and how they feel rewatching this footage almost two decades later. The film could be viewed as a study of the way technology materialises memory, or the way we frame and reframe our pasts. However, what eventually emerges from these conversations is a profoundly moving Insight into the reality of living with epilepsy, with As Mine Exactly proving that when it comes to understanding the lives of others, listening is the real key to empathy.

The post Exploring empathy through virtual reality at LFF appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments