As the son of one of Iran’s most beloved filmmakers, releasing your first film into the world must be a daunting experience. Yet with Hit the Road, a Cannes Quinzaine 2021 favourite and winner of Best Film at last year’s London Film Festival, Panah ‘son of Jafar’ Panahi has carved out a space for himself in the Iranian cinematic canon that is entirely distinct from his father’s work.

A tragicomedy centring on a family – Mum, Dad, an adorably chaotic little boy, and Farid, the taciturn older son forced to flee the country – who are driving to the Iranian border, Panahi’s directorial debut is a wry yet gut-wrenching exploration of the aftermath of political oppression, a tender ode to the lives of everyday Iranians forged under impossible circumstances. We spoke to Panahi about the film’s play (or lack thereof) with genre, the appeal of the car as a cinematic space, and the importance of leaving some things unsaid.

LWLies: Hit the Road is such an unusual Iranian film in so many ways – it’s a road trip film but there’s also a magical realism element towards the end. Can you tell me about your approach to genre?

Pahani: When I was writing it, I wasn’t even thinking about genre. I think I subconsciously knew not to, because genre cinema has so many rules that can box you in. But when the film premiered at Cannes and people started asking me about the road trip elements, it was only then that I realised I had made a road trip film. Before that, it hadn’t even occurred to me.

Reading people’s responses has been so interesting: one person said it takes you through all these different genres, like this novel form of cinema. It’s fascinating, because I hadn’t thought about switching genres – magical realism, science fiction, whatever – at all. What I learned, really, was the importance of giving myself over to my unconscious, to whatever feels right in the moment. To write and not limit myself.

At the same time, the car plays such a crucial role in the film – it reminded me a little of your father Jafar Panahi’s film Taxi Tehran in that respect. What was it about the car as a cinematic space that appealed to you?

This was something else I noticed in the response: people thought the car and the rural setting must be a deliberate cinematic reference, whether to Abbas Kiarostami or to my father. Maybe it’s something you have to live in Iran to understand, but the way we use cars is very different from anywhere else. It’s not even a cinematic idea, it’s just daily life. Because we don’t have a good transport system, and we’re somewhere where the basic rules of free society aren’t really respected, people take refuge in their cars. There’s much less policing: if your headscarf slips you won’t get in as much trouble…you can listen to your own music. They’ve become like our second homes. I think I unconsciously came to this setting because my own life, like a lot of other Iranians, is like this; we have to craft our own spaces of peace.

I’m interested in what it’s like as a filmmaker to make this kind of social critique while still working in the country – do you find that tension difficult?

I didn’t exactly look at it like that. For me, the sort of situation shown in the film can be a vehicle for exploring more universal themes, whether those we intend or ones the audience bring themselves, to use cinema to give these themes shape. But of course, you always worry that you’re touching on [political] ideas but not really doing anything. You walk around with this guilty conscience, like “what am I even doing? We’ve already heard these conversations, what am I adding?”

What remains, I suppose, are the simple, special relationships that come out of and through tragedy, and that can humanise the story for the audience. Maybe they’ll look at the news stories they normally pass over and, in the light of these characters, sit with them longer. That’s really all a filmmaker can do: beyond that, it’s out of our hands.

Would you say, then, that the characters came first or the story?

The idea for the story – although I can’t say exactly when or where it started – is something just constantly in our lives. Close friends, acquaintances…all our conversations are about how we can’t be [in Iran] anymore, that we need to make a future somewhere better. It’s always been in the background but as time has gone on, certain events happened that made me think I can articulate these ideas cinematically. Like when my sister left Iran, we were playing old songs and singing along together, trying not to show how sad we were. It made me realise that I can tell a story that, although the political side is important, can also speak to these other experiences. A family taking their child somewhere where the future is uncertain: there’s a universality to that story that I wanted to tell.

So much of this film is rooted in silence, both in terms of its release and Iran’s censorship laws but also in its very structure: we don’t hear Farid speak until 15 or 20 minutes into the film, and we aren’t told what he’s done to have to leave. Why is silence so central?

Contrast and paradox were really important to me when making this film: joy alongside sadness, silence alongside chaos. Regarding Farid, he’s made his decision: he knows he has to go and he’s accepted his fate.

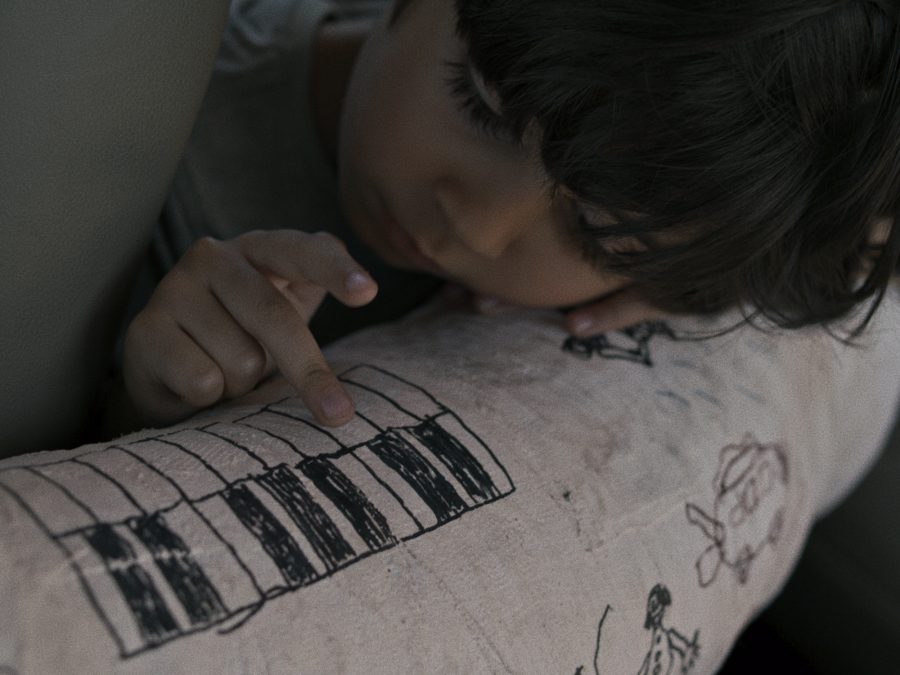

For me, Farid was largely an excuse to bring the rest of his family together. The main focus is really on these three other people; the person leaving largely becomes a cinematic device. I tried to code it throughout: at the start, we see Farid outside of the car, he’s already become separate from his family. Even in the car, he doesn’t have dialogue and we edit it so you don’t really see him. I wanted this unconscious sense that he’s not really a participant in the events of the film – he’s already gone.

Did you know what it was Farid had done?

Yeah, I knew. His decision was almost my own, one I would have made myself. But I felt if I said explicitly why he’s leaving, I would limit the story to a particular context and close off the character. Even in the context of Iran, I wanted Farid’s story to be about a person wanting to fly the nest and live their own life. It becomes universal. But if I had said: “Well, his trouble is that he was involved in protests and got arrested”, then a viewer from, say, New Zealand, would maybe stop relating. Like: “This is not my story. This is another story, the story of people in those countries with those problems”.

At the same time, this feels like such a profoundly Iranian story: this idea of exile and not being able to go back is such a common experience.

One hundred percent. I don’t think you can find a family now who hasn’t experienced this. All of us know someone who has gone through it.

The post Panah Pahani: ‘A lot of Iranians have to craft our own spaces of peace’ appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments