The Norwegian capital has been a character in almost all features made by Oslo-raised Joachim Trier, often masked as merely a backdrop to the delicately dissipating human relationships which are a trademark of his films. Trier’s account of the city is imbued with a quotidian romanticism that bleeds melancholy once carefully dissected.

For him, Oslo is first and foremost its people and that’s precisely why a few of his films – Reprise, Oslo, August 31st, and The Worst Person in the World – are known as the ‘Oslo trilogy’. In all three the protagonists grapple with their own identity as twenty/thirty-something men and women, representative of a middle class gifted with what seems like endless possibilities, and the reality of wrong choices amidst privilege and despair. It is through inhabiting lives and surroundings in equal measure that the films claim their arresting intimacy.

An archiving impulse marks the opening of Oslo, August 31st, where old council films meet personal accounts including those of the filmmaker and his co-writer, Eskil Vogt. “It’s not Oslo, it’s the people I remember”, says the narrator and through that sentiment of reminiscence the film commemorates the lonely and the lost who haunt the city, similar to the film’s protagonist. A recovering drug addict (Anders Danielsen Lie) rides a taxi through a tunnel, the end of which reveals a metamorphosing Oslo: enlarged construction sites and shiny buildings perk up as they orchestrate the skyline anew.

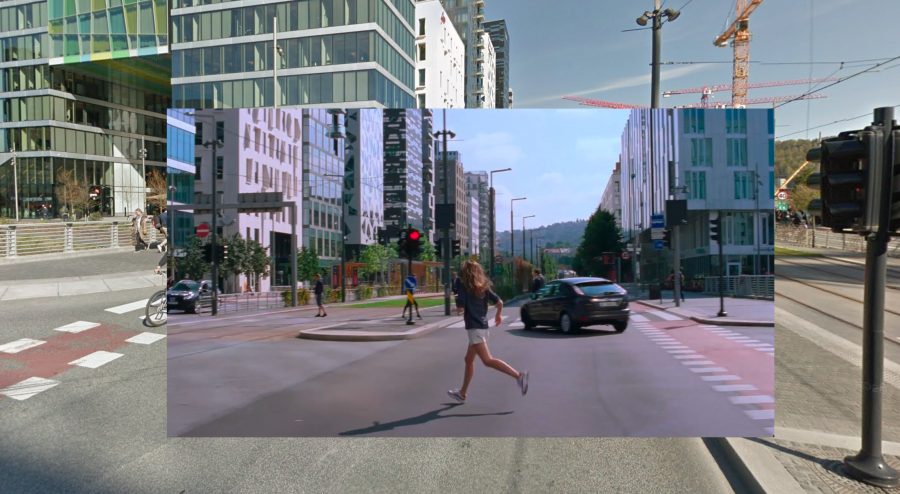

This way, the film documents the repurposing of the waterfront – Fjord City – in favour of high-rise buildings, well before its completion in 2016. Now known as the Barcode Project, the site plays a central role in Trier’s latest film, The Worst Person in the World. Despite its contested reputation among locals, the Barcode fosters the burgeoning love between the protagonist Julie (Renate Reinsve) and the charming barista she leaves her former relationship for, Eivind (Herbert Nordrum).

By imbuing this newly-built high-rise part of town with the couple’s amorous thrill, Trier affirms both a locus for new memories and an ever-changing Oslo, the streets of which can be retraced again and again for the pleasure of discovering its familiarity anew. Julie’s run through the city in a “frozen time” sequence reproduces the real, almost straight, path from her ex Aksel (Danielsen Lie)’s bohemian apartment in the posh area of Uranienborg towards an Åpent Bakeri coffee shop – Eivind’s workplace –in the hip and gentrified Barcode in the eastern part of central Oslo.

It is also symbolic for the move between a relationship with an older man who is also an established comic book artist, and her infatuation with a cheery and unpretentious man her age. As Julie and Eivind finally kiss, we catch a glimpse of another symbol of the ‘new’ city, the Oslo Opera House, which served as a backdrop to one of the emotionally explosive scenes in Trier’s supernatural thriller Thelma.

Greenery is equally important for the trilogy, as all films feature parks as locations of narrative importance. In Reprise and Oslo, 31st August we see Frogner – Oslo’s biggest park in the west part of the city – giving shelter to tough conversations about life and death. Candidly, we lurk around its swimming pool (Frognerbadet) at dawn and explore the curiosity of the so-called ‘echo spot’ in the middle of Vigeland Sculpture park, while the characters celebrate an endless summer night.

The Worst Person in the World, however, prefers to mute all dialogue in the parkland, leaving us with the minutiae of looks and gestures instead, as the couple greet the sunset atop the St. Hanshaugen hill, famous for its big midsummer celebrations.

The coexistence of new and old refers to both the life and relationship choices Julie struggles with, and to the terrain of Oslo’s ever-changing image. Her meandering path of self-reinvention mimics the psychogeographic walk she takes in the film’s first act. Julie leaves a lush reception at the top of a hill overlooking the city, and this is Ekerberg, one of the oldest inhabited places in the city (Gamle Oslo).

A quiet, wandering walk along the scenic Kongsveien road encapsulates the intimacy one establishes with a road to nowhere. In a singular moment, Julie pauses to gaze at the panoramic view and the camera’s slow 180-degree pan circles back to her face; it’s as if that ‘new’ Oslo has been imprinted on her expression of melancholic reverence. At the wedding party she crashes at the end of her wander, she meets Eivind for the first time. Their playful flirtations expand beyond the house walls and a mischievous promise not to meet again turns the unremarkable corner of Arups gate and Egedes gate into a gravitational centre for their secretly shared world.

In Reprise and Oslo, 31 August, Oslo doubles as an antagonist – it’s the place against which the male protagonists define themselves. This sense of national and personal belonging complicates the relationship between people, their social environment and city itself. The protagonists inhabit affluent neighbourhoods in the west of Oslo, such as Frogner, Majorstuen and St Hanshaugen, and they often feel trapped in the familiar tidiness there.

In the third film, however, there is a noticeable shift taking place. Alongside Julie’s individualisation, the film adopts a wider view of what Oslo already is, keeping in with the changing times. In mapping the city, Trier returns to places anew and a locational overlap between the films attests to a singular Oslo within the trilogy. It is the same city and it isn’t. As a significant other, knowing it better means knowing more of it.

Joachim Trier’s films can be read as urban storytelling, even if the director himself hesitates to align with a sociological or analytical point of view. Instead, he simply documents, on the one hand by readily including familiar Oslo spots, and on the other, by translating a certain mood – or the way light bounces off a certain street in summer – onto the big screen. In his act of chronicling the here-and-now lies a desire to arrest time, much like Julie’s solitary run through a motionless city in a sequence, both pushing against realism and re-enchanting the real already there at the turn of a corner.

The post Oslo through the eyes of Joachim Trier appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments