Music biopics are often uncomplicated affairs. Perhaps due to the trade-off required in order to secure the rights to an artist’s back catalogue, a great many function like brand extensions rather than dramatically engaging examinations of the people behind the music. Lip-service may be paid to their ‘flaws,’ but the narrative will ultimately bend over backwards to create a redemption arc because of the music they created. More than the results being antithetical to convincing drama, they’re often just plain boring. Mythmaking in a manner that sands off a subject’s specific aura to make them more like everyone else who’s been the subject of one of these. A Notorious B.I.G. biopic and a Tupac Shakur biopic should not be functionally interchangeable from one another, and yet…

This is why I remain drawn to 24 Hour Party People, director Michael Winterbottom and screenwriter Frank Cottrell Boyce’s 2002 biopic about Factory Records and its mastermind, Tony Wilson (Steve Coogan). In keeping with Wilson and Factory’s post-modernist ironic approach to their own image, the film frequently calls attention to the shortcuts, genre conventions, and outright fabrications it utilises in the telling of its story. “When given the choice between the legend and the truth, print the legend,” as Wilson narrates upon one such instance.

But rather than the showy meta fourth-wall breaks, the subversive angle that really sticks out to me is a lot more mundane. Instead of painting Wilson, the Factory crew, and artists like Joy Division and Happy Mondays as visionary geniuses with few character flaws, the film’s irreverent comedy-drama tone instead allows a more abrasive, human picture of its subjects to form. To freely act like, as they often lob at each other, “cunts.”

With regards to the depiction of Tony Wilson, that’s not entirely a surprise. Alan Partridge, Coogan’s most famous creation, was partly inspired by Wilson so there’s expectation for some Partridge-esque behaviour. Winterbottom and Boyce both clearly admire the idea of Tony Wilson, but they’re also frequently just as willing to puncture his visionary aura by demonstrating his occasionally myopic worldview or near-complete lack of business savvy.

An early scene between Wilson and first wife Lindsay has him narrate in voiceover that they both wanted “a couple of kids” only to immediately have Lindsay insist that she doesn’t want kids. Wilson keeps pressing the idea, demonstrating the self-serving central-protagonist egotism which makes up one of his fatal flaws. He thinks of himself as a revolutionary capable of frightening the system, but his journalistic career remains stuck interviewing dwarfs who clean elephants. He constantly talks himself and his artists up in ways that are supposed to make him sound cultured, but reuses the same few reference pools: the Last Supper for sub-par attendance, comparing Shaun Ryder’s lyricism to W.B. Yates, Boethius’ philosophy about wheels.

His Factory inner circle frequently call him out in ways that presage the company’s eventual downfall. Alan Erasmus laughing about the “Blue Monday” single artwork costing the label money with every copy sold; Martin Hannett quitting as soon as he takes one look at the Haçienda; Rob Gretton attempting to fistfight Tony when told about the £30,000 table in the Factory office. But they too argue with each other, hopped up on a near-endless stream of drugs, and engage in poor decisions (like Rob indulging New Order’s desire to record Technique in Ibiza during monsoon season) so they don’t really have a high ground. Almost all of Hannett’s screen time consists of him shouting obscenities at the bands under his charge rather than demonstrating his artistic process.

Then there are the bands. The Happy Mondays Shaun Ryder has a crippling drug dependency which climaxes in the ruinous recording of Yes, Please! Joy Division don’t exactly come out smelling of roses, either. Ian Curtis is introduced yelling “WILSON, YOU CUNT!” from the other side of a bar and aggressively getting in Tony’s face. Peter Hook nonchalantly displays little concern when Ian has a seizure at the end of one gig, even trying to loot the man for his cigarettes. At another, they stand by watching the opening act A Certain Ratio and spend the entire time shit-talking their labelmates.

One could argue that the comedic angle of the film acts as its own defence mechanism, playing up the cast’s less-desirable qualities for laughs but still excusing it all under the guise of comedy. Not so different from the “but the music, man!” justification of more straightlaced biopics and ultimately not that subversive. Undoubtedly, its treatment of Ian Curtis’ mental health struggles and everyone’s drug addictions tends towards the glib; a reflection of dated early-00s attitudes.

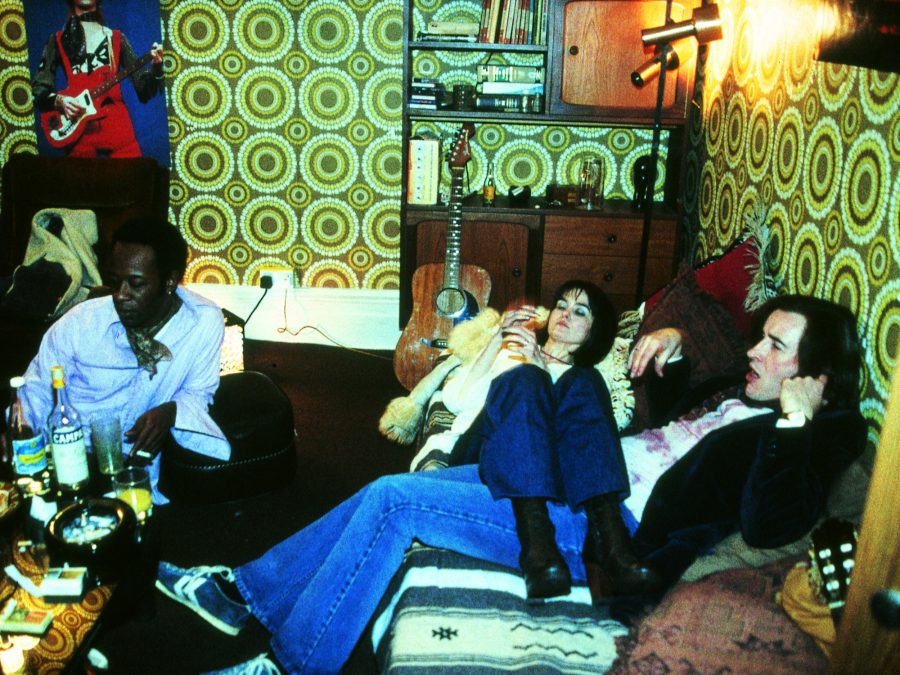

But Winterbottom and Boyce’s approach creates something somewhat truthful; that most of the people involved in Factory were a bunch of idiots, screw-ups, and assholes who happened to get lucky by being in the right place at the right time with the right music. Winterbottom’s filming style communicates that chaos, utilising a cinema verité approach which darts around muddily-mixed scenes. It might still be a form of mythmaking, but a richer portrait of these characters emerges when they’re treated as the multifaceted people they were. Anton Corbijn’s 2007 biopic Control has a more respectful depiction of Ian Curtis, but the version from 24 Hour Party People is more memorable and interesting.

This kind of anti-reverential characterisation is perhaps best epitomised by the film’s final sequence. The morning after the Haçienda’s final night, Tony Wilson goes up to the roof and smokes some strong weed. He has a vision of God, physically and aurally resembling Wilson, who tells him that “basically, you were right.” Turning back to some of his Factory crew to brag about the experience, they express mocking disbelief about the affair. “Well, it was written in the Bible, ‘God made Man in his own image,’” Tony tries to rationalise. “Yeah, but not a specific man,” Rob fires back, before the conversation turns to the quality of the gear they’re smoking. Attempted profundity brought crashing back down to reality.

The post How 24 Hour Party People offered an anarchic spin on the music biopic appeared first on Little White Lies.

0 Comments